Social innovation, effectual reasoning, and developmental evaluation.

“An effectual worldview is rooted in the belief that the future is neither found nor predicted, but rather made.”

I am sharing the first 10 pages of an evaluation report and this slidedeck from a workshop session at the 2015 National Sexual Assault Conference.

I am so grateful to have been a part of an initiative of Pittsburgh Action Against Rape to disseminate sexual violence prevention messages among male athletes. I got to study the evidence-based violence prevention program Coaching Boys Into Men, and grapple with ideas about about social innovation, effectual reasoning, and developmental evaluation with prevention champion Julie Evans and her team.

This is page 1 of the end-of-project report. It was amazing to lead, learn, and coach alongside my social change collaborators at PAAR as we evaluated their implementation of Coaching Boys Into Men. (I am easily excited by evaluation, in general, but this project ALL-CAPS JAZZED ME UP.)

This is page 2, The Table of Contents, for the final evaluation report commissioned by PAAR. Contact Julie Evans at PAAR to learn more about findings not shared here.

Coaching Boys Into Men as Social Innovation

Coaching Boys Into Men (CBIM) is an evidence-based prevention program for male coaches and athletes aimed at stopping sexual and relationship violence before it happens. Throughout the season, coaches facilitate a series of conversations with their players about: respect, personal responsibility, insulting language, disrespectful behavior towards women and girls, digital disrespect, consent, bragging about sexual reputation, aggression on and off the field, pressure & intimidation in relationships, setting boundaries in relationships, modeling respect & promoting equality.

YAAAS! I super love Coaching Boys Into Men

“A social innovation is a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than current solutions. The value created accrues primarily to society rather than to private individuals. ”

CBIM, like most sexual violence prevention efforts, qualifies as social innovation because it is a more effective, efficient, sustainable, and just solution to the social problem of sexual violence than many existing criminal justice responses to sexual violence perpetration.

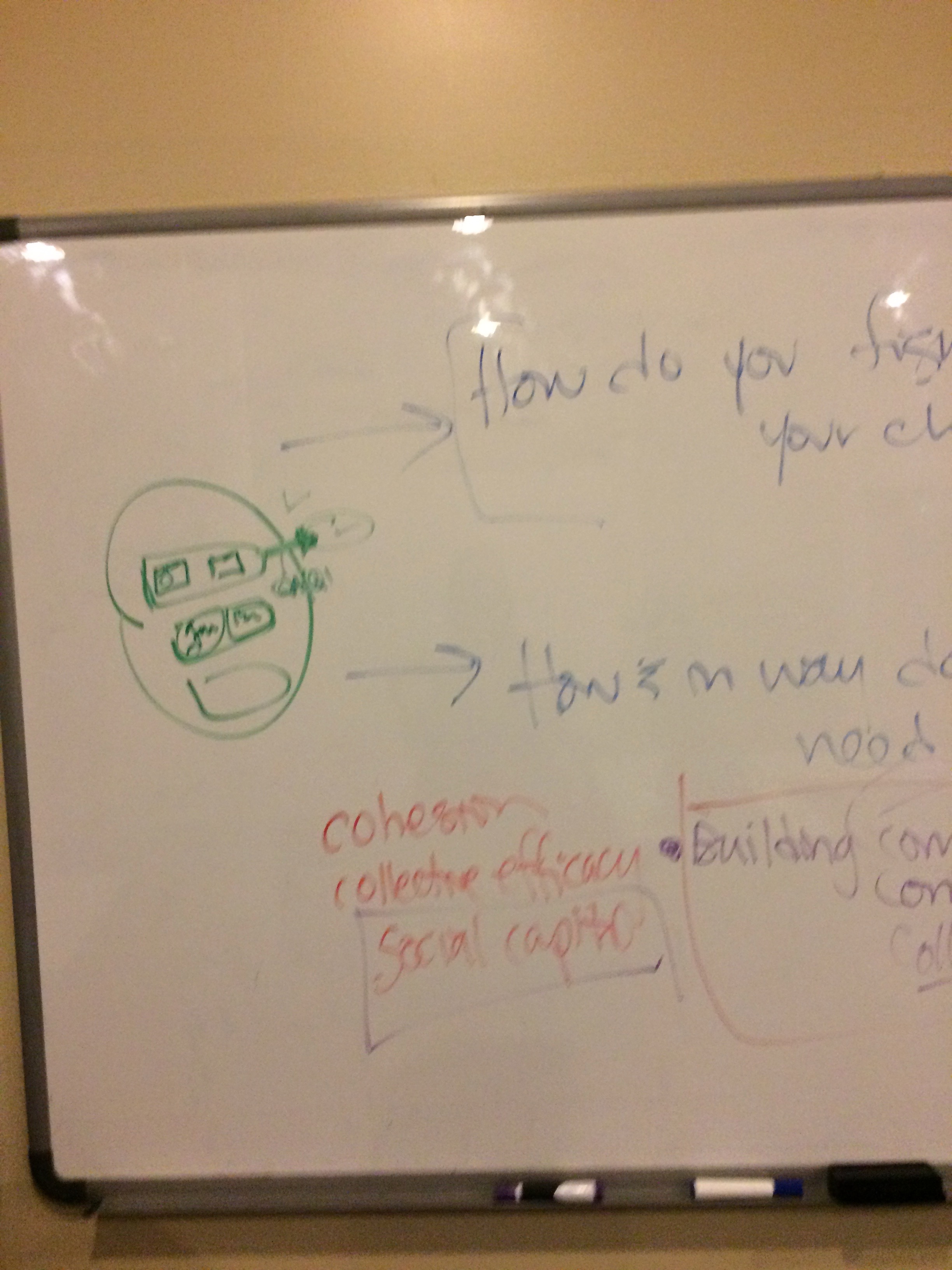

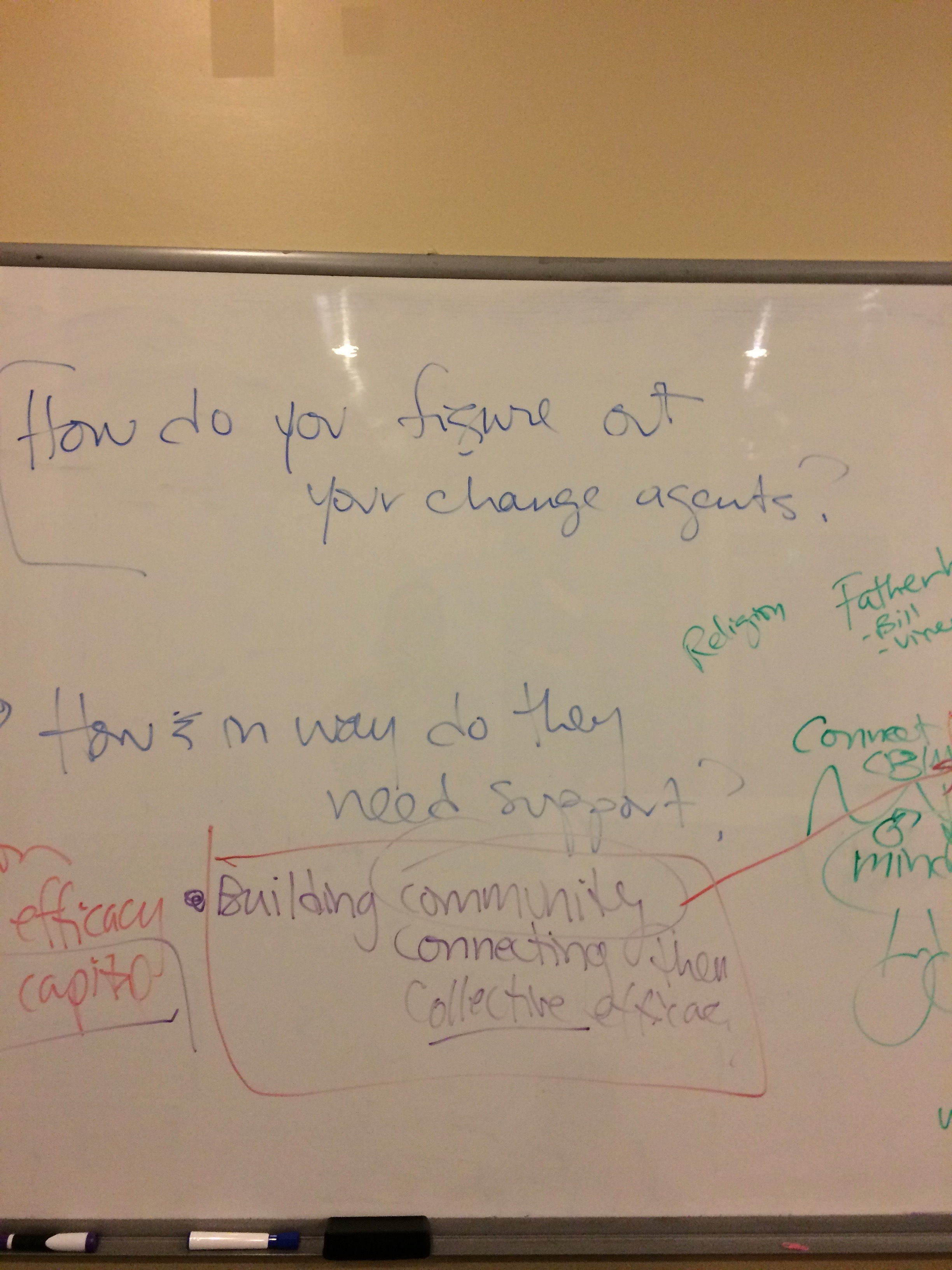

Here's evidence on CBIM's effectiveness, documented by Dr. Liz Miller and colleagues. Because CBIM had already been field tested, PAAR's evaluation questions did not focus on program's effectiveness. Rather, PAAR's team needed answers to questions such as these scratched across this whiteboard in the South Side Flats. The goal was to recruit high school coaches, secure the coaches’ agreement to implement CBIM, and support those coaches in carrying out CBIM with their teams.

We designed an implementation study around the question — How do you find and support change agents? — to evaluate the prevention support PAAR was providing to coaches. Below is the one-pager of our conclusions.

Using Developmental Evaluation, we were able to both improve the prevention efforts as they evolved as well as document the value of PAAR's prevention work across Pittsburgh and Allegheny County.

The Final Step of the Public Health Model Requires a Shift in Thinking

Whereas the first three steps of the public health approach to violence prevention — define the problem, identify risk and protective factors, and develop and test prevention strategies — often rely on controlled research designs and causal reasoning, the last step — assure widespread adoption — requires a shift in thinking. The primary task is “selling” new ideas, beliefs, behaviors, or social policies to targeted groups.

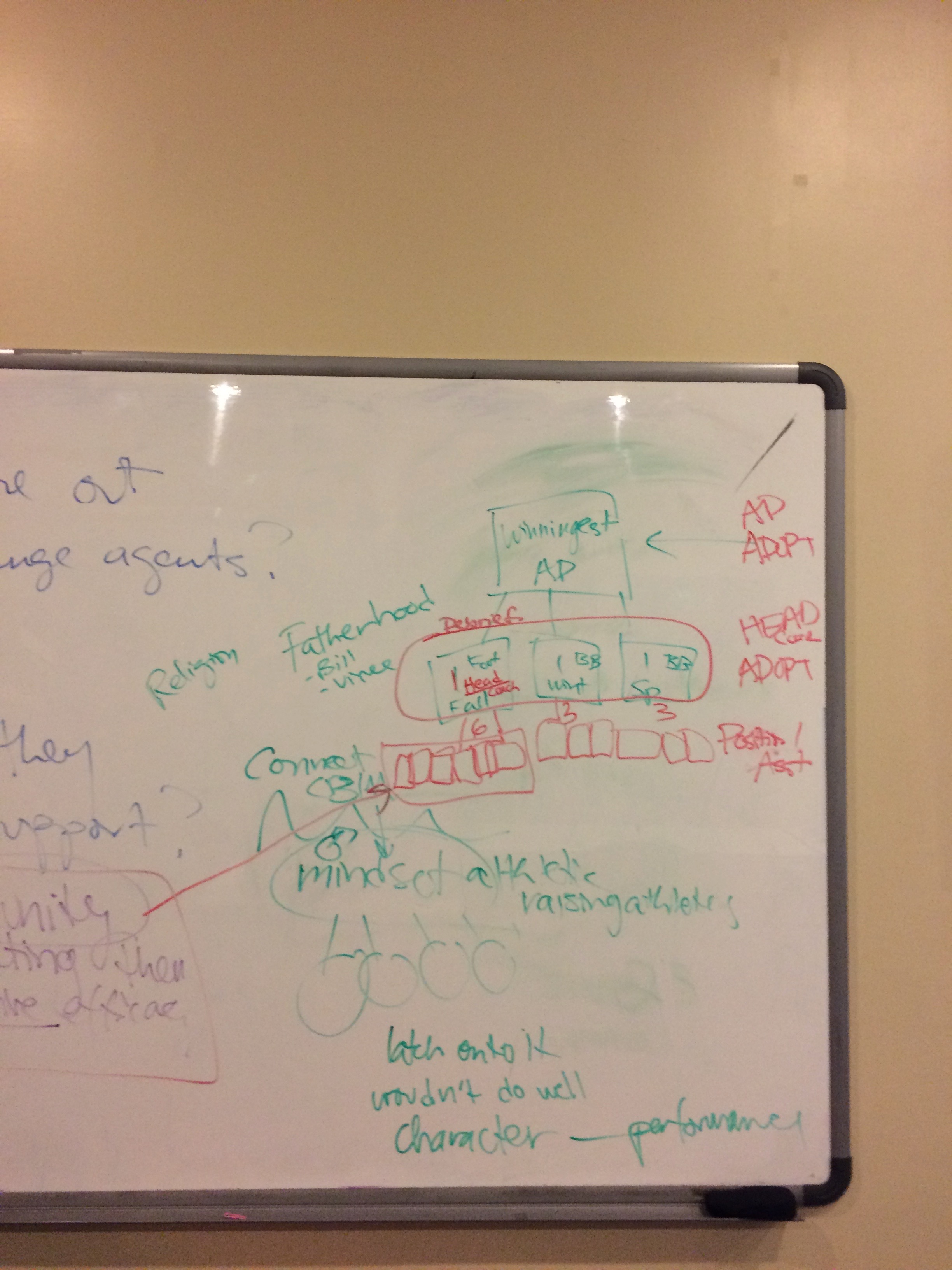

Revisiting the diffusion of innovations theory was helpful in understanding coaches of male student-athletes as early adopters (EAs). EAs watch and follow innovators on the cutting edge. They, too, are visionaries and risk takers so the unknown appeals to them and they are continuously looking for new opportunities. Because EAs tend to be leaders and role models in their social settings, they can provide the “stamp of approval” that reduces risk for the early majority and helps spread acceptance of the innovation.

We also got to apply some ideas from the society for effectual action.

“Social innovators shape the unknowable future with principles of effectual reasoning.”

As shown in the figure at the top of this post, effectual reasoning stands in contrast to causal thinking. As I listened to PAAR's prevention team, which included male high school coaches, talk about their work, it struck me that they were thinking more like entrepreneurs than educators or program managers. In the early stages of this work, I asked, “how are you training your early-adopting coaches?”

I learned that, in addition to holding classroom-style training, PAAR coaches were also meeting one-on-one in public spaces like parking lots, basketball courts, and training rooms to do “on-the-fly” training with other coaches they wanted to adopt the program. It was an important selling point that the CBIM program could be worked right into what coaches were already doing, without a lot of training. Requiring interested coaches to come to a day-long training workshop, or even half-day workshop, felt tricky.

Evaluating PAAR’s efforts to take CBIM to scale required a new way of thinking about program development and evaluation. The team at PAAR was willing to embrace a new idea; and so we worked together to apply the five principles of Professor Sarasvathy’s concept of effectuation, what I refer to as effectual thinking, to our CBIM evaluation project.

On Page 6 of the CBIM report, the five effectual principles are contrasted with more traditional causal thinking. Causal thinking undergirds traditional program development, management, and many forms of goal-based evaluation.

The Work Unfolded as a Series of Implementation Trials

Over the course of two years, the PAAR coaches applied Bird-in-Hand to leverage existing relationships in order to implement multiple rounds of CBIM, which are described on page 7 of the report shown below. For example, the first implementation trial made use of an existing partnership that PAAR had implementing prevention programming in a junior high school setting. After each implementation trial, the evaluation team convened in order to facilitate a learning and goal-setting process to guide the next implementation trial.

This project made use of existing relationships between PAAR and middle schools, high schools, and local universities and colleges to implement three rounds of CBIM in a variety of new settings (CBIM was originally designed for high school coaches).

Social Innovations Can Be Challenging to Evaluate

Complex real-world conditions in communities demand our patience and persistence even when we are evaluating the most “tried-and-true” programs. When the program is unknown (as CBIM was), questions conventional beliefs about gender and sex and masculinity (which are deeply personal topics), attempts to alter high school football (which is sacred in many communities), and is implemented by coaches who are not getting paid to do the program, it becomes that-much-more challenging.

““Complex environments for social interventions and innovations are those in which

what to do

to solve problems

is uncertain

and key stakeholders are in conflict about how to proceed.” ”

Developmental Evaluation Acknowledges the Complexity of Social Innovation

In designing evaluation activities that were consistent with the effectual reasoning leading PAAR’s CBIM implementation work, we incorporated some of Scriven’s (1991) early ideas about goal-free evaluation (GBE), and leaned on Patton’s (2011) more recent guidance on developmental evaluation (DE).

Page 8 of the report summarizes how both innovation and complexity are accounted for in the emerging practice of DE.

Developmental Evaluation Is Centered on the Innovators' Commitment to Make a Difference

For PAAR's CBIM Implementation Project, developmental evaluation helped us: 1) come to terms with the messy space we were working in, and 2) reframe expectations around how to document value, significance, and worth of the work. We used two metaphors when discussing this project, which are summarized on page 9 of the report.

As illustrated by the “Road Trip Advisor” and “Iron Chef” examples, effectual principles and developmental evaluation require a willingness to try new things as well as tolerance for ambiguity.

While the developmental evaluation (DE) approach is "not the solution to every situation," we successfully applied DE principles to gather and process information that created insight; make decisions about new program elements, e.g., PAAR's Coach-the-Coach prevention support; and ultimately, document the value and worthiness of PAAR's community prevention work.

Page 10 of the report, shown below, summarized three of the most significant and valuable change levers in PAAR’s efforts, followed another 49 pages of evaluation data that provided evidence of the hallmark successes of the project.

It was my absolute pleasure to join Southwest PA says NO MORE, the FISA Foundation, and PAAR to work on providing men and boys some tools for preventing sexual violence and modeling respect and equality.

To talk to me about how you might apply effectual thinking in your work; or to share your experiences with DE; please comment below or send me an email. I’d love to hear from you!